- Home

- Peter Shelton

Climb to Conquer Page 2

Climb to Conquer Read online

Page 2

Dole and company not only admired what the Finns were doing in February 1940, they also wondered aloud if there might not be an important lesson there. The Finnish resistance was “a perfect example,” Minnie wrote later in Birth Pains of the 10th Mountain Division, “of men fighting in an environment with which they were entirely at home and for which they were trained.” What if Germany decided to invade North America? Would we be able to defend our northern border? In winter? In a winter like the one raging outside that very night?

There had been no firm indication that Hitler’s territorial ambitions extended across the Atlantic. But American paranoia, following two decades of isolationism, ran wild, and not without justification. German U-boats were sinking merchant ships bound for England. There were documented cases of Nazi-inspired sabotage and propaganda here at home. The publication in 1939 of Nazi Spies in America, by FBI agent Leon Turrou, caused a near panic, especially in New York. Turrou claimed that evidence gained through the use of a lie detector, a new technology (not yet discredited), proved the German-American Volksbund, a cultural organization based in New York, was actually a front for a Nazi spy ring. In a January 1939 article for the Charlotte News, the writer W. J. Cash enumerated what most Americans believed to be true, that “the Nazis do have an extended chain of spies scattered throughout this country, in shipyards, in ammunition plants, in key industrial spots, in air bases, in the army and navy—all busily engaged in stealing and smuggling out information designed to give the high command in Berlin a complete picture of our readiness for war and our points best open to attack.”

Would Germany attack? Hitler’s dream of Lebensraum, of “living space” for a pure Aryan race beyond the borders of the Fatherland, had always pointed east to the fertile plains of the Ukraine. And he seemed to be moving in that direction with the Anschluss, the forced merger with Austria in 1938, and then the annexation of Czechoslovakia and the rout of Poland a year later. But what if Hitler’s armies were simply unstoppable and his appetite grew for dominion beyond Europe?

Minnie Dole and friends certainly wouldn’t have been alone if they had engaged in a bit of speculation, a round of fireside “what-if?” What if England and her still-vast empire were forced somehow to surrender to the Nazis? In 1940 the British navy still ruled the waves, but her army and air forces, purposely small and reeling from the horrors of 1914 –18, were not up to challenging a continental German war machine that had been modernizing for half a decade. What if England were to fall and, along with her, our massive neighbor to the north?

If Hitler could use Canada as a staging area, surely the United States would face a daunting threat. Minnie Dole knew his history and his geography. All four New Englanders at Johnny Seesaw’s that night knew that an invasion route from Montreal south held real strategic promise. It had happened before. British and French troops fought up and down the Champlain Valley during the French and Indian War, some of the time on snowshoes. The British had raided down the broad valley separating Vermont and New York as far south as Fort Ticonderoga during the American War of Independence. And then barely thirty years later, they tried it again before they were stopped at the Battle of Plattsburgh. Had the redcoats not been defeated there, they would have had a straight shot at Albany and the Hudson River. A quick thrust down the Hudson would have brought them to New York City, effectively severing the Northeast from the rest of the nation. “What chance would we have today of defending against such an attack,” the skiers wondered aloud, “especially in winter in mountainous New England?”

Not much, they concluded. Particularly against Germany’s Jaegers, Hitler’s mountain troops. The Reich counted three specially trained mountain divisions at the beginning of the war and would add as many as eleven more as fighting spread into Scandinavia, the Balkans, and the Carpathians. All three original mountain divisions had contributed to the “lightning war” in Poland the previous autumn. The United States had no troops trained and equipped for either vertical landscapes or cold weather. Our most recent conflicts abroad had been in Cuba and the Philippines, and almost all of our training facilities were in the Deep South, Hawaii, and Panama. The U.S. Army, small and underequipped as it was, was a tropical army. The most recent military study to be found on equipment for winter warfare had come out of Alaska and was dated 1914. It included advice on the proper use of the polar bear harpoon.

Dole and Langley decided that evening at Johnny Seesaw’s to write the War Department and offer the services of their respective organizations in the nation’s defense. The premise was rather vague, but Dole in particular had something valuable to offer. The National Ski Patrol System had in slightly more than a year become a grassroots network of some three thousand members—all hearty outdoorsmen and women—spread across the nation’s northern tier. Ski patrollers might help map the northern frontier or train Army draftees in skiing technique. Or the patrol itself might be organized into volunteer units that could later be incorporated into the Army. The National Ski Association, for its part, might serve as a clearing-house for mountaineering information. Actually, neither Dole nor Langley knew exactly how they might be of use. The point was to make the case for winter-ready troops. And in Dole’s case, that plea would soon become an obsession.

The reply to Dole and Langley’s first letter, which arrived later that spring signed by an underling, was in Dole’s words little more than “polite derision”—“The Secretary of War has instructed me to thank you . . .” and so on. The officer wrote that his department fielded every sort of wacky if well-intentioned offer, including one from a man who claimed he had invented bullets that shot around corners.

Minnie Dole refused to be discouraged. Born in 1900, he had grown into a soft-faced man with a high forehead and studious wire rims who was partial to silk ascots and a walnut burl pipe. But regardless of his gentle exterior, Dole could be imperious; he was a patrician by birth and temperament, a man used to getting his way. The only other circumstances in his life that had similarly thwarted his will had also had to do with war. At seventeen, when the United States entered World War I, he tried to enlist in the ambulance corps, but his father had refused to give his permission. Minnie was “sick with frustration” when he heard the battle stories of former classmates fighting in France. As soon as he turned eighteen, he applied to Officer Training School but arrived at Fort Lee, Virginia, to the wailing of sirens and the cheering of cadets who had just heard news of the Armistice.

The National Ski Patrol was born out of Minnie’s personal response to two skiing accidents. The first occurred on New Year’s Day 1937, in Stowe, Vermont, when Dole fell awkwardly in tricky wet snow and heard bones in his ankle snap. There were no trained ski patrolmen on the mountain in those days, no rescue sleds. It was hours before his friends were able to haul him, shivering and near shock, down the hill on a scrap of roofing tin. Two months later, Minnie was hobbling around on crutches when he learned that the same friend who’d helped him down the hill in Stowe was now dead, having flown into the trees while downhill racing on the Ghost Trail near Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Devastated, Minnie turned his grief to work and, not much more than a year later, in March 1938, with encouragement from Roger Langley and help from the American Red Cross, announced the birth of the National Ski Patrol System. He organized courses, designed certification exams, standardized practices on the hill—including the placement of rescue toboggans—and wrote the first Red Cross Winter First Aid Manual. By 1939, the NSPS had thousands of members in ninety-three chapters, at least one chapter in every state where snow regularly blanketed the hills.

Now, after watching the Finns fight on skis, Minnie Dole was convinced the United States needed specialized cold-weather and mountain troops. The Germans had their Jaegers, the French their Chasseurs Alpins, the Italians their Alpini. The United States should be similarly prepared—either for defense or to fight on foreign mountains—and Minnie, with his organizational skills and grassroots connection to American skiers, could h

elp. Over the next twenty months, he rained letters on official Washington, two thousand of them by some estimates, pecked out on his Royal typewriter in the small home office that doubled as National Ski Patrol headquarters.

Dole followed every lead with the tenacity of a crusader. When one avenue appeared to close him off, he tried another, or he went over the top. He wrote directly to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and to Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall and to Secretary of War Henry Stimson. The Army, in turn, resisted at first the very idea of specialized troops. This wasn’t the Army way, and considering the limited money and time, there were more pressing matters, namely the need to build regular infantry divisions from scratch. Dole persisted. In one letter, he wrote, “If the Army will not entertain [the idea of mountain troops], I am seriously thinking of organizing a Voluntary Group myself and putting such Corps through a month’s training next winter, with the aid of foreign teachers who are familiar with maneuvers as carried on in their own countries.”

By “foreign teachers,” Dole meant the many ski instructors who had emigrated to the States from Central Europe during the 1930s. Some had fought in the mountains in World War I, and others had served in mountain divisions after the war. Now they were the vanguard of American skiing. As the first U.S. ski schools were being organized, these Austrians and Germans and Swiss became the first professional instructors—at Peckett’s-on-Sugar-Hill in New Hampshire, at Stowe, and at Sun Valley, Idaho, which opened in 1936 with the world’s first chairlift, an engineering marvel based on overhead-cable systems for loading banana boats. The United States had produced a handful of fine, homegrown skiers in the early years of the sport, but the imported Europeans were the shining stars of the sudden 1930s skiing boom.

One might have expected skiing to decline during the Depression years, but in fact, the numbers grew dramatically. In 1936 Time magazine referred to alpine skiing as “a nationwide mania” and opined that “winter sports in the U.S. have ceased to be a patrician fad and have become instead a national pastime.” Between the late 1920s and the late 1930s, the number of American recreational skiers ballooned from around twenty thousand to at least two hundred thousand.

Time may have overstated skiing’s egalitarian appeal. Most of the best skiers still came from well-to-do families who had traveled in Europe and could afford to send their sons and daughters to college, where the most serious competition (and coaching) was to be found. But the explosive growth did cross class lines. The biggest reason was the invention of the continuous-loop rope tow. Before, everyone had had to make the sweaty, if soulful, uphill hike on skis for the much briefer pleasure of sliding back down. Cross-country and downhill skiing were essentially one and the same; it was the arrival of lift-served skiing that ultimately separated the two endeavors. A ride to the top, even if it did cost a dollar a day, made all the difference. The first U.S. rope went up at Woodstock, Vermont, in 1934, and within three years there were hundreds of tows coast-to-coast. They were cheap and relatively easy to install; many were powered by Model T Fords, which could come down off their blocks in summer and be driven away.

Suddenly, farmers in hill country with fields and orchards that held good snow had a way to make a little extra money in the winter months. Farm wives with an extra bedroom or two hung SKIERS WELCOME signs in the window. Roosevelt’s New Deal work crews, the Civilian Conservation Corps, cut ski trails on virgin state lands. Snow trains brought skiers from the cities out into the country for a day or a weekend, and then hauled them back, partying all the way, on Sunday night.

Skiing’s glamour trickled down to a growing middle class that tapped into its fashion and lingo and songs. No other winter sport threw off such sparks; it was exhilarating, healthy exercise in an era with no superhighways leading to warmer climes, no television, no Internet. Plus, it was a great way to meet the opposite sex, even before the invention of stretch pants in the 1950s.

The final piece in skiing’s amazing growth spurt was Minnie Dole’s “foreign teachers.” Americans needed instruction in “controlled skiing,” and the resorts, particularly the more exclusive ones like Peckett’s and Stowe, were willing to import the best. The acknowledged masters came from the Arlberg School, in Austria, where Hannes Schneider had perfected a teaching progression based on the snowplow, the stem turn, and the stem christiania—terms that soon worked their way into the American skiing lexicon. These men brought their alpine charm, along with the first instruction books and films, to an enthusiastic reception in the States even as talk of war darkened the mountains at home.

By mid-year 1940, with progress slow at the War Department, Minnie took it upon himself to compile a skiing manual that might aid in training a future ski army. He used parts of existing texts by Otto Lang, an Austrian protégé of the great Schneider; by Benno Rybizka, another Arlberg instructor; and by the Swiss Walter Prager, who coached the Dartmouth College ski team. Minnie also began collecting information on ski mountaineering and equipment with the help of the California mountaineer Bestor Robinson.

Meanwhile, in April, Germany invaded Norway, occupying all of her major port cities. A relatively small force of German Jaegers held its ground for more than a month against heavily reinforced British counterattacks in the fjords at Narvik, proving again the value of trained mountain troops. In May, Hitler launched his western offensive, rolling quickly through Belgium and Holland and into northern France. And in June, when France capitulated, Nazi armies marched east into Romania to secure that country’s oil resources. In the Far East, the Japanese conquest extended beyond Manchuria into the rest of China, and Japanese war planners openly coveted the raw materials, including oil, in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), in French Indochina, and in British-held Malaya. By September, the Japanese would formally join the Axis powers, Germany and Italy, forming the Tripartite Pact. In less than a year, the war had widened into what John Jay, 10th Mountain Division public relations man, would later call “total war.” Most of the planet would be drawn in, and battles would be fought in every kind of weather and terrain. Mountains, which had in past wars served as barriers to be avoided or bypassed, would surely see fighting in this total war. Minnie Dole was certain of it.

The barrage of letter writing intensified and finally paid dividends during the stifling late summer of 1940, when Dole and NSPS treasurer John E. P. Morgan traveled to Washington to see the Army’s top man, Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall himself. Marshall met them in his summer dress uniform and mirror-polished black cavalry boots. The irony of the scene could not have been lost on any of them, sweating in the September heat and talking about ice and snow.

Marshall listened more than he spoke, and at the end he told his visitors that a decision had been made to keep some existing U.S. Army units in the snowbelt through the coming winter to experiment with training and equipment for cold-weather fighting. Clipped and formal, he said he appreciated Dole’s interest and very likely would call upon the NSA and the NSPS for advice on gear and ski-teaching technique.

Marshall never told Dole what had changed the Army’s thinking, whether Dole’s letters had finally been persuasive or whether the lessons of Finland and Narvik had tipped the scales, or a combination of the two. For whatever reasons, Marshall had apparently become a convert. In a formal letter of November 9, 1940, he charged:

the National Ski Patrol, acting as a volunteer civilian agency, to become fully familiar with local terrain; to locate existing shelter and to experiment with means of shelter, such as light tents, which may be found suitable for the sustained field operations of military ski patrol units; to perfect an organization prepared to furnish guides to the Army in event of training or of actual operations in the local areas; and to cooperate with and extend into inaccessible areas the antiaircraft and antiparachute warning services.

Despite the military’s distaste for working with civilian organizations, Marshall had let Dole and the National Ski Patrol into the mix. There had been no promise

of a mountain division, and indeed it would be another year before the commitment was made to create one, but, in Minnie’s phrase, “the pot was bubbling.” The reality was, Army higher-ups knew nothing about mountains and skiing. They needed help, and they knew it—and they would get it that first winter from enlisted men and civilians who’d grown up in the snow.

Marshall’s order created six Army “ski patrols” (not to be confused with the NSPS patrollers who volunteered at ski areas around the country). These were small, detached units patched together from the skiers and woodsmen already in established infantry divisions. Each patrol was given $1,200 to purchase ski equipment locally, not nearly enough to equip each man but enough, it was thought, to train groups of men in turn.

The 1st Division patrol operated out of Plattsburgh Barracks in upstate New York. They skied strictly cross-country on the rolling trails built for the 1932 Olympics at Lake Placid. Their instructor was three-time captain of the U.S. Olympic jumping team, Rolf Monsen. The men liked the training, understandably; it was what they had done for fun as kids. Their commanding officer, Col. John Muir, liked it too. “I believe that ski training is an asset,” he wrote in a subsequent report. “Like the Texan’s six-shooter, you may not need it, but if you ever do, you will need it in a hurry, awful bad.”

Men from the 44th Division trained at Old Forge, New York, under newly inducted Pvt. Harald Sorenson, an Olympic skier from Norway. These soldiers were challenged to races by local snowshoers—some of the best in the Adirondacks—who considered their mode of locomotion more versatile than skis. The snowshoers set the courses, which included lots of uphill and tight trees, but the skiers won every time, proving that skis, as ungainly as they might seem, were faster for general snow travel.

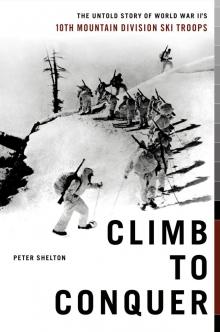

Climb to Conquer

Climb to Conquer